December 19th, 2025 • 8 mins read

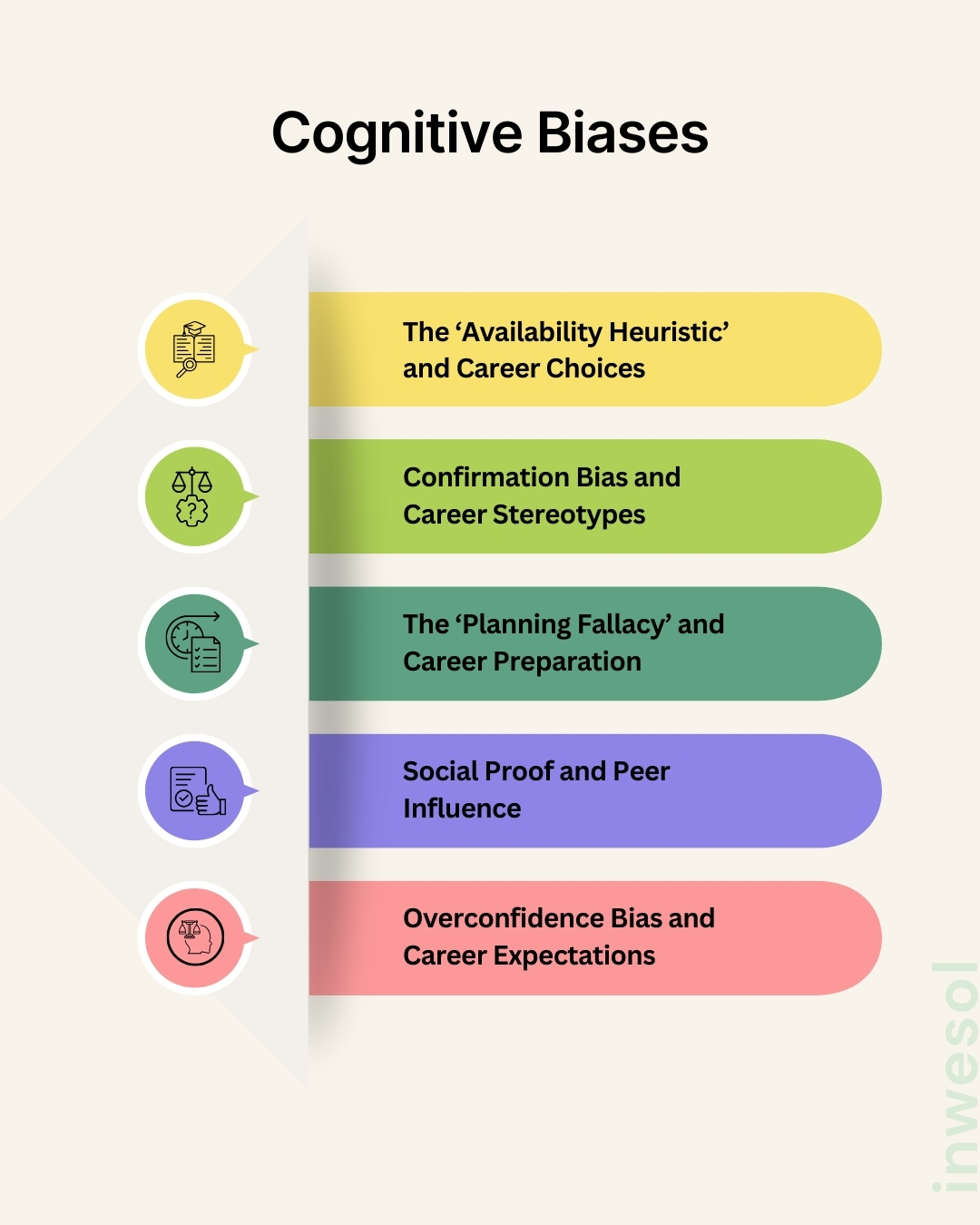

What Are Cognitive Biases? How Do They Shape Career Decisions

Choosing a career path is one of the biggest challenges teenagers and their families face. In theory, career decisions should be based on clear factors like job market demand, personal strengths, and long-term financial security.

But research shows that our thinking is not always that straightforward, cognitive biases often shape these choices in powerful ways (Kahneman, 2011). Let’s understand what cognitive biases are and how they affect career decisions.

Understanding Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases are patterns in thinking that divert people away from fully informed and logical decisions. They can be useful in daily life, but when it comes to careers, they can sometimes cause teenagers to make choices that aren’t in their best interest (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). For teenagers moving from school to work, these biases can strongly influence their career paths, often without them even realizing it.

Since the teenage brain is still developing until the mid-twenties, young people are more vulnerable to certain biases that affect how they make decisions (Steinberg, 2013). Parents, even with their experience and good intentions, also carry their own biases into career conversations. This creates a mix of influences that can either help or get in the way of making the best career decisions.

1. The ‘Availability Heuristic’ and Career Choices

One common bias in career decision-making is the availability heuristic, which is the tendency to give more weight to options or events that come easily to mind (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973). For teenagers, this often means being drawn to careers that are highly visible in media, popular culture, or their surroundings, while overlooking other options that might actually suit them.

Social media and entertainment strongly shape these perceptions. Careers in entertainment, sports, or tech entrepreneurship often look more appealing because they get so much attention (Bandura, 2001). At the same time, equally rewarding paths in healthcare support, skilled trades, or logistics may be ignored simply because they don’t get the same spotlight.

Parents can also reinforce this bias. They usually share career advice based on what they know from their own experiences or what is considered as a ‘stable’ path in their network. For instance, a parent in finance may highlight banking and investment careers but know little about newer fields like data science or renewable energy. This limited information can unintentionally restrict career exploration.

2. Confirmation Bias and Career Stereotypes

Confirmation bias is the tendency to look for information that supports what we already believe, while ignoring evidence that goes against it (Nickerson, 1998). This bias has a strong effect on how teenagers and parents view career options, often reinforcing gender roles, cultural expectations, and assumptions about which careers are “suitable.”

For teenagers, this can mean rejecting career paths that don’t match their self-image or social group.

For example: A student who thinks they are “not good at math” may avoid careers in data science. They might focus only on early struggles with math while ignoring signs of improvement or strengths in related areas.

Parents also show confirmation bias when assessing their teenager’s career interests, especially if those interests clash with family expectations or cultural norms.

Studies show that parents’ career expectations strongly shape their children’s choices, sometimes even more than the teenager’s own skills and interests (Dietrich & Salmela-Aro, 2013). This effect is often stronger in families where certain jobs are seen as more prestigious or secure than others.

3. The ‘Planning Fallacy’ and Career Preparation

The planning fallacy is the tendency to underestimate how much time, effort, and resources are really needed to complete something (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979). This often shows up in how teenagers and parents prepare for careers, leading to poor planning and unrealistic expectations.

Teenagers may think career success will come quickly after graduation. They often underestimate the effort needed to build professional skills, network, and prepare for the job market. As a result, they may focus only on finishing their degree while ignoring important things like gaining practical experience, developing professional skills, or exploring different career paths.

Parents can add to this bias by assuming that career preparation today works the same way it did when they were younger. They may overlook how much the job market has changed and how important digital skills, personal branding, and continuous learning have become for success (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2014).

4. Social Proof and Peer Influence

Social proof is the tendency to look at what others are doing to guide our own choices, especially in uncertain situations (Cialdini, 2006). This bias strongly affects how teenagers make career decisions. Since teenagers naturally seek validation from their peers and elders, they may choose careers for social acceptance rather than personal interest or ability.

This often leads to groups of students following the same popular career paths. Parents also experience social proof when guiding career choices. They may suggest careers based on what is respected or admired in their community, rather than focusing on their child’s unique skills and interests. This can pressure teenagers into careers that boost family reputation but don’t truly match who they are or what they want.

5. Overconfidence Bias and Career Expectations

Overconfidence bias, the tendency to overestimate one's abilities and chances of success, commonly affects teenage career planning (Dunning, 2011). This bias can lead to unrealistic career expectations and professional challenges.

Overconfidence in one’s ability to succeed in highly competitive fields without fully understanding the requirements or competition involved can result in insufficient backup planning, skill development and poor risk assessment in career decision-making. While supportive encouragement is important, unrealistic optimism can hinder effective career preparation and planning.

Strategies for Reducing Bias in Career Decision-Making

Recognizing how cognitive biases shape career choices is the first step toward making better, more informed decisions. Families can use a few simple strategies to reduce these biases and improve the decision-making process.

- A. To counter the availability heuristic, teenagers should be exposed to a wider range of careers beyond the ones they already know. This could be done through activities like talking to professionals in different fields, job shadowing, internships and using career assessment tools.

- B. To address confirmation bias, teenagers can be encouraged to look for information that challenges their assumptions. This means exploring both the positives and negatives of different career paths instead of only focusing on what matches their current beliefs.

- C. To reduce the planning fallacy, it helps to create realistic timelines and preparation plans. Breaking down career preparation into small, clear steps and regularly checking progress against achievable goals can make the process more practical and effective.

Conclusion

Cognitive biases often shape how teenagers and parents make career decisions, sometimes limiting exploration and preparation. By understanding biases like availability heuristics, confirmation bias, planning fallacy, social proof, and overconfidence, families can make more thoughtful and fulfilling choices.

With structured exploration, open-minded thinking, and realistic planning, teenagers and families can make career decisions that align better with personal interests, opportunities, and long-term satisfaction.

Want to Read More on Self-Discovery and Career Motivation?

Self-Discovery: The Foundation of a Meaningful Career

Psychology of Career Motivation

References

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology, 3(3), 265-299.

Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2014). The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. W. W. Norton & Company.

Cialdini, R. B. (2006). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. Harper Business.

Dietrich, J., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Parental involvement and adolescents' career goal pursuit during the post-school transition. Journal of Adolescence, 36(1), 121-128.

Dunning, D. (2011). The Dunning-Kruger effect: On being ignorant of one's own ignorance. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 247-296.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263-291.

Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175-220.

Samuelson, W., & Zeckhauser, R. (1988). Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1(1), 7-59.

Steinberg, L. (2013). The influence of neuroscience on US Supreme Court decisions about adolescents' criminal culpability. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(7), 513-518.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5(2), 207-232.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124-1131.